College of Social Work partners with Japan on co-parenting

The College of Social Work has a rich tradition of international collaboration. Dr. Tomi Gomory has worked for many years in Romania and the Czech Republic, speaking at conferences and publishing scholarly manuscripts pertaining to his research there. Dr. Neil Abell has formed deep connections in Northern Ireland, conducting seminars and researching “the Troubles”—historical conflicts between Ireland’s Catholics and Protestants and continues to form international partnerships as the FSU College of Social Work’s International Programs Director. Dean Jim Clark, Dr. Amy Ai, Dr. Bruce Thyer, and Dr. Shairi Turner recently returned from China, where they were featured at an international symposium on disaster and trauma. And our newest faculty member, Dr. John Mathias, spends his summers in India researching the connection between environmental and social justice issues.

Continuing this tradition of global partnerships, the Institute for Family Violence Studies forged a new relationship between the FSU College of Social Work and Japan’s Tokyo International University (TIU) and Taisho University (TU). The partnership began with Japanese researchers’ interest in the prioritization in U.S. law that a child maintains contact with both parents under appropriate conditions following a divorce. This practice stands in stark contrast with Japan’s cultural assumption that after the dissolution of a marriage, only one parent will continue raising the child. Joint custody or court-mandated shared parenting, does not exist under Japanese law.

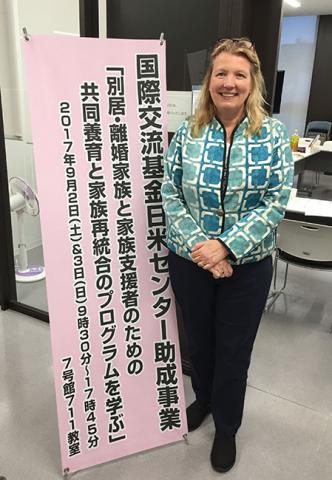

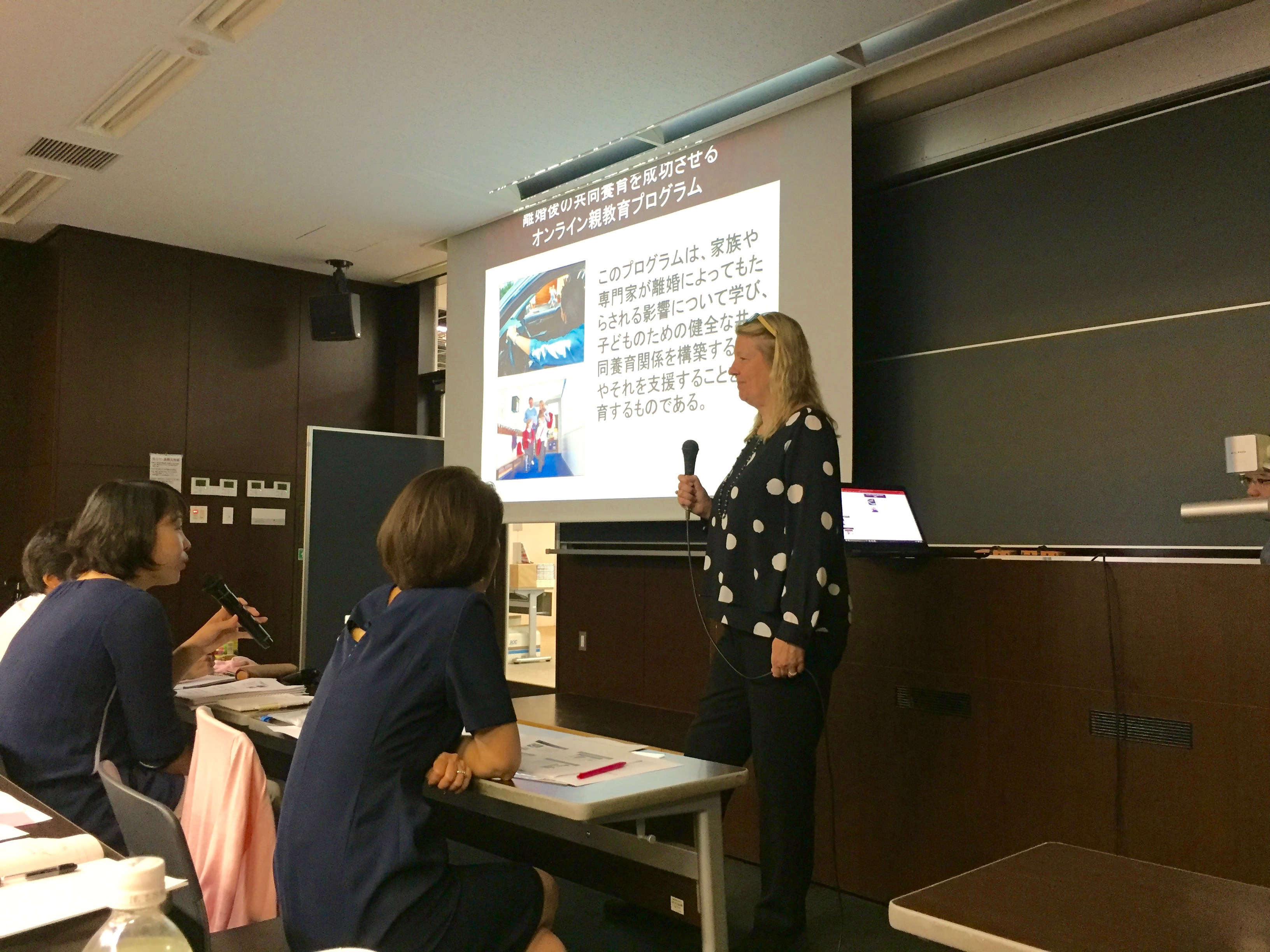

The Japan Foundation Center for Global Partnership funded the TIU/TU development of an international seminar on post-divorce parenting in Japan. Professors Akira Aoki and Noriko Odagiri invited me to speak at the seminar about FSU’s project Successful Co-Parenting After Divorce, an online training offered free to parents through a grant to FSU from the Vandermark Foundation (https://coparenting.fsu.edu). Co-presenter Dr. Anthony Ferraro, a doctoral graduate of Florida State University and now an assistant professor at Kansas State University also worked on FSU’s project. Other seminar speakers included a representative from the U.S. Center for Missing and Exploited Children, who spoke about international child abduction and is an expert in play therapy for traumatized children.

The Japanese researchers wanted to create a similar online training for separated parents in Japan, as roughly a third of marriages end in divorce. Their approach has been to find existing material that can be adapted for a Japanese audience and to develop a Japanese team that can change cultural assumptions about what constitutes a child’s best interest. The cultural and legal differences between the United States and Japan, however, are quite stark.

Although the divorce rate in Japan is lower than in the U.S., hundreds of thousands of Japanese children grow up with only one parent—the one with whom the child had the deeper relationship during the marriage. A number of cultural dynamics contribute to this single-parent phenomenon:

- Japanese work culture values long work days, limiting the time that a working parent can spend at home with family;

- the lack of maternity and paternity leave;

- a culture that discourages mothers of young children from working; and,

- a stigma attached to divorced mothers who encourage their ex-husbands to share in co-parenting.

Because of these significant differences, seminar participants were invited to think creatively to determine which components of the FSU training might be adaptable to a Japanese audience.

The seminar’s 100-member audience consisted of lawyers, supervised visitation providers, Non-Government Organization executives who want to increase children’s opportunity to see both parents, and numerous “left behind” mothers and fathers who have little to no access to their children. After viewing FSU’s training, these individuals gathered to share their ideas. The framework of a concrete plan emerged from the conference, centered around a website, similar to the resources guide on FSU’s co-parenting website, that collects all of Japan’s existing resources for divorcing parents. Some of the suggested titles for this website included “Children First, Japan” and “Family Resources for Divorced Parents.”

Participants also agreed that the cultural emphasis on grandparent support of grandchildren should be an important part of the new collaboration between the universities and the community on co-parenting. Powerful videos should be developed that normalize increased child contact with the “left behind” parent, emphasizing that children can benefit from having two involved parents. Moreover, components of the website could support custodial parents in their efforts to maintain the child’s contact with the “left behind” parent. Finally, policy proposals developed by the group and supported by the universities could encourage the government to update laws to allow more contact between children and their non-custodial parent as long as that parent has not been violent or abusive.

These efforts are still incremental. The modest vision of nominal increases in child-parent contact—two or three visits a month that last for several hours— was seen as a substantial improvement over the current standard visitation of monthly two-hour visits (at most). All researchers are committed to continuing their partnership as the Japanese universities develop their proposed model of increased child-parent access. I look forward to participating in that important work.

An added bonus of my trip was exploring parts of Japan. Here are three highlights:

- Celebrating France’s ties with Japan, this smaller Statue of Liberty overlooks beautiful Tokyo Harbor.

- Kyoto is home to over 1000 Shinto and Buddhist shrines and temples. The Allies did not extensively bomb Kyoto during WWII, so the holy buildings survived the war.

- The Shinkansen, or Japanese bullet train, travels up to 200 mph.

Karen Oehme, J.D. is the Director of the Institute for Family Violence Studies and a Distinguished University Scholar at the College of Social Work.