College of Social Work Hosts Panel on Child Welfare in Native American Communities

In November, the Florida State University College of Social Work held a virtual event focused on "Child Welfare in Native American Communities." The event marked November as Native American Heritage Month and was a significant opportunity for the College's social work community to familiarize itself with the needs and issues facing a highly marginalized part of the child welfare system.

"African-American and American Indian or Alaska Native children are at greater risk than other children of being confirmed for maltreatment and placed in out-of-home care," indicated a recent report from the Children's Bureau, an office of the Administrative of Children and Families.

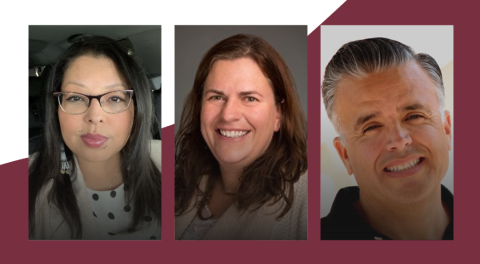

The College of Social Work welcomed experts in child welfare in Native American communities:

- Shannon Smith, Executive Director, Indian Child Welfare Act Law Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- Shana King, Community Outreach and Parent Mentor, Indian Child Welfare Act Law Center and Member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation.

- Michael Huesca, Chief Executive Officer of Paternal Opportunities, Programs and Services, San Diego, California and Indigenous Mexican-American

During the event, the conversation centered mainly on understanding the recent ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court to uphold the Indian Child Welfare Act. The act was part of efforts from the federal government in the 1960s to establish new policies geared towards tribal self-determination for Native American and indigenous populations of the United States after decades of actions by the U.S. government to eradicate Native American heritage.

The Indian Child Welfare Act was enacted in 1978 to protect the rights of Native American children to live with their families and to stabilize and stabilize/cultivate continued tribal existence. The act served as a corrective policy after decades of damaging and unwarranted child welfare practices that separate Native American children from their families, tribes and culture.

"We have an elder in our community who often told me that, 'you are where you are when you need to be," said Ms. Smith during the discussion. "I had this really powerful moment today, a feeling of being where I'm supposed to be today because we're actually a year out from when the U.S. Supreme Court heard the Haaland v. Brakeen decision."

The Supreme Court ruled in the case Haaland v. Brakeen in favor of upholding tribal sovereignty under the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, which was threatened by three separate child welfare cases challenging the protections and prioritization of Native children to be kept within their own families and communities.

Ms. Smith particularly highlights the importance of the concurrence, or appellate decision, of Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, who noted that Native American tribes entered into agreements and treaties with the federal government in good faith regarding their land, resources and education that were not upheld and federal policy was even used to destroy families. "And the easiest, or most powerful way to destroy a community is through children," She noted. "American Indian children were removed from their families and places with non-native families with a very purposeful intent to ensure that they were assimilated into a different culture."

Historically, a common practice by the federal government was to establish boarding schools to remove Native children from the influence of their families and culture and this was a policy in place for more than 100 years.

Mr. Huesca noted that the case of Haaland v. Brakeen, "Felt like another attack. It felt like another broken promise" for Native American and indigenous communities.

He also shared his memories of his grandmother coming to Southern California, recruited to work in fruit orchards but also subjugated. "She would tell me that they were not allowed to speak their language. They were also not encouraged to practice their spirituality, or their religion, or their medicine," he shared. "Indians were getting killed and so the more you looked like an Indian, the more likely you were possibly going to be harmed. And so Mexican indigenous people were encouraged as quickly as possible to learn the language."

"Gorsuch recognizes that this documented history was very purposeful in trying to destroy the future of tries, trying to destroy the future of American Indian families and that this history needs to be taken into account as to why the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed," Ms. Smith added.

"I feel like the core of it is putting humanity back into the work," agreed Mr. Huesca. "That's to me what it's really about, embracing a way of life."

Ms. King also agreed with these perspectives as someone who has personally been impacted both by the current legislation and the loss of culture and language.

"It's really important to me and I'm a champion for equality because it keeps your identity intact," she underlined. "A lot of the traditions and our culture is lost. I feel that personally, I feel that when I go home. We are doing our best to keep it alive. But that is just a result of what happened to our people."

Although the upholding of the Indian Child Welfare Act is a victory of tribal sovereignty, the discussion recognized the loopholes through which many native children and communities fall through the cracks. "You're only eligible if you are a part of a federally or state-recognized tribe, which we have to understand," said Mr. Huesca, noting the misunderstanding that many small Native tribes lack casinos or income streams that allow for a higher level of autonomy and resources.

The Indian Child Welfare Act provides a federal mandate for minimum standards required in tribal child welfare proceedings in any state. The act allows individual states to enact counterparts, which can be additional state mandates if they increase protections for Native children and families.

"Because of tribal sovereignty, ultimately the decision as to whether or not a child is an Indian child really has to come from the tribe," Ms. Smith explained. "The more complicated part is not who gets to make the decision. That's incredibly clear. It's what kind of information you provide to the tribe for them to make that decision."

Resources, or the lack of them, pose a significant challenge when providing the necessary information related to Native child welfare cases, even down to names, demographic information and a family's connection to a tribal community. Much of this stems from the loss of culture, language, family ties, and traditions.

Navigating the applicability of the Indian Child Welfare Act remains complicated, even when it relates to custody disputes between parents and third parties. Still, Ms. Smith underscored some gold standards that can be applied to ensure equality and support for Native families for practitioners when working with them, including:

- The involvement of fathers in a deliberate and purposeful way.

- Active efforts to be responsive with compassion and empathy for Native families, especially in times of crisis.

- Placement preferences that recognize and honor a child's connection with their family and community.

- Being informed and knowledgeable about the Indian Child Welfare Act and the rights of Native families and children.