Field Placements Provide Insights into Food Insecurity

Learning about large social issues like food insecurity in a classroom can provide tremendous insight into some of the most urgent needs of disadvantaged communities, but it is through field placements that social work students put a face to the community needs they seek to alleviate.

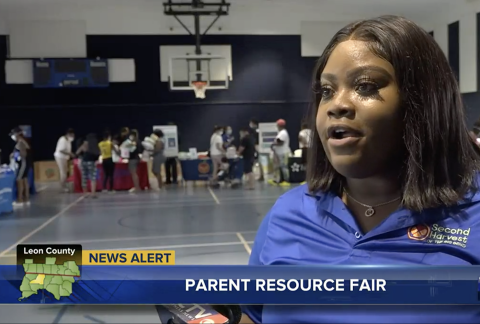

This summer, three College of Social Work MSW students on the social leadership track were able to gain experience organizing and advocating to reduce hunger. Graduate student Mallory Adams is in the dual master’s degree pathway for social leadership and public administration and interned with the Leon County’s Office of Human Resources and Community Partnerships. Her peers, Jacobi Peavy and Emmanuel Routsis both interned with Second Harvest of the Big Bend (Second Harvest). Jacobi is also enrolled in the dual master’s degree pathway for social leadership and public administration, and Emmanuel‘s MSW pathway focuses on social leadership.

Each has had unique personal and professional realizations about community needs and the work done by local organizations seeking to improve Floridians' lives surrounding Florida’s capital city.

A field placement at Second Harvest gave Jacobi Peavy insights into the complexities of organizing a large, sophisticated nonprofit organization, allowing her to learn a wide array of experiences. She described sitting in and speaking up at Feeding America meetings, leading and organizing the organization’s first Community Parent Resource Fair along with its monthly Neighborhood Empowerment Event.

One of the key roles organizations like Second Harvest plays is to not only distribute food to local food pantries and partnering organizations but to bring resources into disadvantaged areas to meet the basic needs of community members. It is not only food deserts that plague disenfranchised communities, but a consistent, general lack of resources that include, but are not limited to medical care, transportation, hygiene items, and other basic needs.

Being a cog in the complicated machinery of an organization addressing hunger not only brought to life familiar social work skills and principles but gave her a personal experience of what she wrote in her capstone paper for her master’s in public administration on “Eradicating Food Deserts and the Detrimental Effects They Have on Health,” coming from a policy-driven perspective.

Not only did the internship give her the hands-on experience of what she had been researching, she even noted how easy it is for communities to fall through the gap related to food insecurity simply by having a convenience or discount store. “It’s important to note,” she stressed, “while people may have access to these stores, these stores are not fully equipped with proper nutritious foods needed for a long healthy life.” While processed or convenience foods may be accessible, many contribute to high rates of chronic illness in food insecure areas.

“Food insecurity is deeper than hunger,” Emmanuel Routsis also noted. “Food insecurity is a consistent lack of resources that leaves individuals stuck in a cycle of need.”

Balancing multiple ongoing projects has resulted in advanced skill development, as Emmanuel and Jacobi both remarked on how being a part of Second Harvest has improved their understanding of needs within local communities and how they can best meet those needs.

Mallory Adams likewise felt the shift from observing the overwhelming need and related tasks to being a part of the social system to alleviate community needs. Hoping to gain experience in local government and its role in the grant funding process, Mallory’s internship with the Office of Human Resources and Community Partnerships has helped her become more detail-oriented and self-confident in her ability to make a difference in the lives of local residents.

One of her greatest insights has been the need to improve community representation at local community organizing meetings and events to relieve food insecurity and address other area needs. Some of these same barriers to sufficient food are also likely to be reasons for a lack of community participation. Key barriers to relieving food insecurity include insufficient income, lack of transportation access, and stigma around receiving public social services. An additional barrier was a lack of community awareness.

Mallory realized that as important it was for her to support these populations and communities, it was even more critical that they have a seat at the table and a part in advocating for their own communities. This meant finding strategies to help make residents more aware of available resources and make more accessible opportunities to participate in community conversations and initiatives.

Although one in four people in the US still experiences some kind of food insecurity, social workers and the network of other helping professions and organizations are on the path toward solution-centered approaches to alleviating not only hunger but food waste and beyond.

“Donations and volunteering are a huge help in getting food out to neighborhoods,” Jacobi suggested as a way anyone can contribute to reducing hunger. Emmanuel also encouraged anyone with knowledge of available resources to share these with friends and family. An example is the extensive lists of community resources on the websites of 2-1-1 Big Bend and Second Harvest of the Big Bend.

With new insights and a new passion for being a part of this solution, Emmanuel, Mallory and Jacobi all see themselves as continuing their involvement in ending food insecurity.